Lula’s campaign in Argentina is mobilizing both Brazilians residing in the country and Argentines anxious for the end of the Bolsonaro government. It reveals two phenomena: on the one hand, a politicization and organizational leap of the Brazilian community in Argentina in recent years, originating from the international reverberations of the June 2013 protests. around Lula’s election in 2022.

I was 25 when the June 2013 protests broke out in Brazil. Lived in Argentina since 2010 worked in a human rights body founded in the military dictatorship. He greatly admired Argentina’s capacity for mobilization and protest, which ranged from the memory acts of the 1976 coup to the frequent union mobilizations, passing through the defense of laws such as that of same-sex marriage. A spirit that did not seem to exist in Brazil, where politics – and human rights – were discussed in universities and offices.

The June 2013 protests changed this state of affairs. These acts, which began in São Paulo against the increase in fares, began to cover many other agendas and spread not only throughout the country, but also in cities abroad with a Brazilian population. In Buenos Aires, an event appeared on Facebook calling for an act at the Obelisk that would head towards the Embassy of Brazil, also located on Avenida 9 de Julio. The organizers were a group of young students with no history of militancy. Soon some people joined who, like me, had a little more experience, including an activist from the Movimento Passe Livre de Brasília. This group disputed the writing of the manifesto to build a text that was less anti-political and more based on the expansion of democracy and rights. The act, however, was a microcosm of June 2013 in Brazil: already at the Obelisk, three militants with T-shirts and the red flag of the MST, an Argentine left-wing party, were immediately surrounded by screams by people with T-shirts from Brazil who made them leave . While we started screaming about the 20 cents, others cursed Dilma Rousseff.

Between 2016 and 2018, when I lived in Brazil, a group of left-wing Brazilians residing in Buenos Aires formed the Coletivo Passarinho. They had a first objective of disputing here the narrative about the 2016 coup against Dilma. Since 2018, they have also assumed with great energy the commitment to the case of the murder of Marielle Franco, a personal friend of some of the Coletivo members. Marielle, black, from the favela, LGBT, became known in Argentine militancy, and several groups and local leaders showed solidarity with the request for truth and justice in the case. Passarinho organized year after year, in March, acts for the anniversary of her death, combining Brazilian cultural expressions with practices learned from the Argentine human rights movement. In 2021 Marielle was honored by the Legislature of the City of Buenos Aireswho installed a sign at the Rio de Janeiro subway station.

Throughout 2018 and 2019, Passarinho held debates and acts of denunciation of the Bolsonaro government. It also boosted the still quite incipient debate in Argentine progressivism on structural racism, forging important alliances with migrant, Afro-Argentine and “brown” collectives. This small-scale construction formed a kind of parallel militant diplomacy, carried out from the bottom up and in a constant manner by people with a trajectory and political training in Brazil who, for personal, professional or political reasons, chose to live and remain in this sister country.

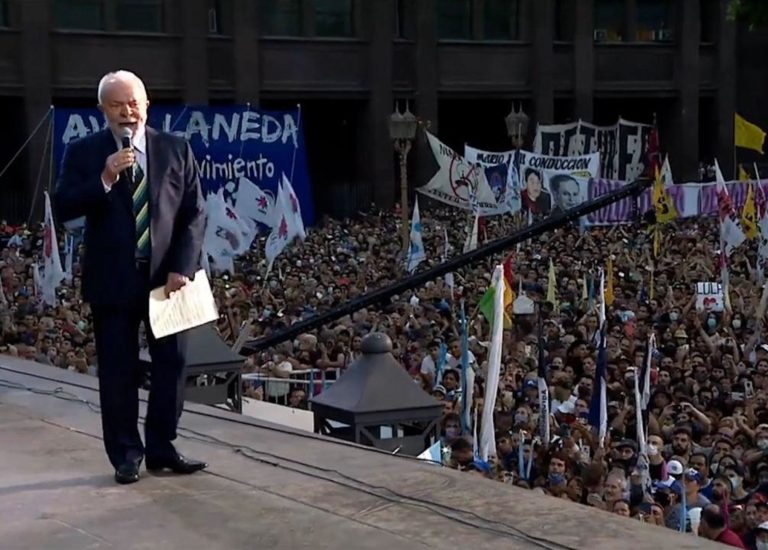

It is in this timeline that the campaign for Lula’s election in Argentina must be located. Although Passarinho is not a party, and people coexist in it who do not always share a single electoral preference, some of the main leaders of the Núcleo do PT in Argentina were and are also active members of the collective. This process of politicization and organization of a mobilized portion of the Brazilian community in Argentina allowed for the formation of cadres who, trained in another political culture and bringing their own agenda, learned to transit in Argentine politics and to build with it.

An informed and strategic campaign

There are now a total of 82,330 Brazilians residing over 16 years of age in Argentina – the data is from April of this year. In the 2014 election, only 6,018 people were registered to vote at the consulate. In the 2018 election, there were 7,143. That number grew to 12,746 in 2022, a 79% increase that must be attributed, in large part, to the work that Lula’s campaign in Argentina did between March and April to get Brazilians to make the request for change to the TSE.

O Core of the Workers’ Party in Argentina, made up of party members living in the country, was created in mid-2021 and held its first public event in December. It managed to bring together more than 60 members of the Workers’ Party residing in Argentina – approximately 20 of whom joined this campaign. It established as its first goal to ensure that more Brazilians residing in Argentina regularized their voter registration and communicated the change of residence to the Superior Electoral Court before the deadline, May 4, 2022.

From the beginning, an informed and strategic campaign was set up. At the beginning of the year, the Nucleus made a formal request for information to RENAPER – Registro Nacional de las Personas, the national body in charge of civil registration, which made it possible to obtain general information on the age, sex and territorial distribution of people with Brazilian citizenship, over 16 years, with temporary or permanent residence in the country. Most are found in the capital of Buenos Aires (42%), followed by the Province of Buenos Aires (20%). Some of the cities with the highest concentration of Brazilians, in addition to Buenos Aires, are Rosario, La Plata, General Pueyrredón (where the city of Mar del Plata is located), Morón, Córdoba and La Rioja. Also noteworthy is the prevalence of young population – 43% are between 16 and 34 years old.

According to Renata Codas, a member of the Núcleo, “the data confirmed the hypothesis we had that most of these people are university students. One of our main campaign strategies was to map and create campaign commands in university centers in cities with the highest concentration of Brazilian residents: Buenos Aires, Rosário, La Plata”.

Brazilian students in Argentina are not typical exchange students, with financial or symbolic resources to study abroad: they are middle or lower middle class people who have not been able to access public or private universities in Brazil, with a predominance of those who wanted to study medicine. The existence of a wide public university system, of quality and free of charge – including for non-Argentines –; and a good and cheap private system, added to the low cost of living in Argentina and the ease of obtaining a permanent residency according to the Mercosur criteria, are factors that make the alternative of living here more viable than attending a private university or passing the selection processes ultracompetitive sectors of Brazil’s public system.

These people are not necessarily organized or politicized – most do not request a change of polling place in order to vote at the Brazilian consulate, the first goal assumed by the campaign. This entry into universities would not have been possible without the support of Argentine student groups, which helped organize and call for meetings that allowed reaching Brazilian students. From the meetings, Whatsapp groups emerged for the coordination of the campaign in each city or university. Another fundamental alliance was with the progressive cultural centers of the cities where the campaign was focused, which in Argentina are organized in a network and which joined the campaign with great interest. Activities included soccer games in Rosario and La Plata, production of material such as t-shirts and stickers, flyers, presence in cultural activities of the Brazilian community, samba circles.

In Buenos Aires, sectoral meetings were also organized with the feminist, anti-racist, immigrant, LGBT and youth movements. Not only PT staff traveled to some of these meetings, but also the president of PSOL himself, Juliano Medeiros, and Guilherme Boulos, whose presence at a large and organized meeting with the Standing Neighborhoods in Buenos Aires helped to inspire and attract new leftist militants to the campaign. A large fundraising feijoada was also organised.

The power of Lula’s campaign in Argentina involves building with a diversity of local political movements with a strong territorial tradition. The principle of regional solidarity has always been very strong in Argentine progressive sectors. It operated fundamentally in situations such as the coup in Bolivia. The interest raised by Lula’s campaign among Argentines, however, also involves a sense of urgency. The country that is experiencing a serious socioeconomic crisis and a situation of strong external debt, and attaches great importance to the return, in Brazil, of a powerful government committed to a developed, sovereign and fair Latin America, which improves the terms of the international insertion of the Argentina.

The Nucleo’s first important victory is already clear, and was expressed in the increase of almost 80% in the number of people able to vote in Argentina. For the day of the election, the PT registered around 30 electoral agents, a list that included affiliated militants and non-affiliated people, like this author. It is the consulate with the most inspectors registered by the party, a function no less so at a time when the president is threatening to contest the election and the functioning of the electronic voting machines. It remains to observe the impact of the campaign on the electoral result. These 12,000 votes may not be very significant for the final result of the Brazilian elections, but they express a lot about the bond between the two countries.

* Camilla Maia holds a degree in International Relations, is a human rights activist in Argentina and is a member of the PSOL’s “Right to the Future” International Program WG

Source: esquerdaonline.com.br