Published 10/31/2025 12:10 | Edited 10/31/2025 19:13

Vietnam has once again become closer to Russia, China and North Korea in a move that reflects the growing strain on its relations with the United States. According to documents and interviews revealed by New York Timesthe Hanoi government resumed the purchase of Russian weapons, reactivated technical-military cooperation agreements and accelerated regional integration projects after successive frictions with President Donald Trump.

The shift occurs in a context of frustration with North American foreign policy, marked by unilateral tariffs, cuts in cooperation programs and a lack of diplomatic predictability.

The rapprochement with Moscow and Beijing is not just a gesture of economic pragmatism, but part of a strategic reconfiguration in Asia.

Analysts point out that Trump, by abandoning commitments made during the Biden administration and treating allies as commercial adversaries, pushed Vietnam into the orbit of Asian powers.

The result is the consolidation of an axis of regional sovereignty that challenges Washington’s dominance and symbolizes the weakening of North American influence in Southeast Asia.

Over the past two years, Hanoi has stopped acquiring US C-130 planes and resumed negotiations to modernize its fleet with Russian Su-35 and Su-30 fighters. Russia, in turn, returned to financing defense contracts with payments in rubles and joint ventures in the oil and gas sector.

This silent but consistent realignment reinforces Moscow’s role as Vietnam’s main military supplier and suggests that the strategy of economic isolation imposed by Western sanctions is far from having an effect.

The episode also marks the return of a nationalist and sovereign imaginary that shaped the modern history of Vietnam.

By celebrating the 80th anniversary of its independence with parades of Russian and Chinese troops in Hanoi, the country reaffirmed its autonomy in the face of external pressure and re-edited a tradition of resistance that dates back to the war against the USA.

The collapse of rapprochement with Washington

During the Biden administration, Vietnam had presented itself as one of the central bets of the North American strategy to contain Chinese influence in Asia. Talks about purchasing C-130 transport aircraft symbolized Hanoi’s attempt to diversify its alliances and reduce historical dependence on Russia.

However, the rise of Trump reversed this situation. The new government abolished cooperation programs on clean energy and combating HIV, raised tariffs on Vietnamese products and interrupted high-level dialogue that began in 2022.

The rupture was worsened by symbolic gestures of disrespect. A Trump Organization development in Hanoi — a golf course and hotel complex built on expropriated land — sparked local protests and fueled perceptions of interference.

At the same time, the 46% tariff imposed on Vietnamese exports was seen as a political coup and a demonstration of economic arrogance. To Lam’s government, which tried to maintain a balance between the powers, reacted by accelerating joint projects with China and resuming military cooperation with Russia.

The geopolitical consequences of Trump’s tariff policy quickly became visible. Moscow took advantage of the diplomatic vacuum and reopened military financing channels, while Beijing intensified its discourse of regional solidarity.

In practice, Vietnam began to participate in parades and joint exercises with Russian and Chinese troops, symbolizing the return of an Asian alliance based on sovereignty and multipolarity.

Contrary to what the White House maintains, bilateral relations are far from a “great relationship”.

In response to questions, spokeswoman Anna Kelly stated that “under President Trump’s leadership, the United States has a great relationship with Vietnam.” The phrase sounds disconnected from reality: behind the scenes, Vietnamese diplomats report distrust and uncertainty regarding American intentions, a feeling that has not been seen since the 1990s.

Military rapprochement with Moscow and the advance of the Asian axis

The resumption of relations with Moscow began discreetly, in 2023, when Vietnamese companies circumvented Western sanctions and maintained maintenance contracts for submarines and air defense systems.

Documents leaked by pro-Ukraine hackers confirmed that the country ordered electronic warfare systems and new fighters, in a deal estimated at US$8 billion.

When Vladimir Putin visited Hanoi in June 2024 — his first trip to Asia since 2018 — he was accompanied by the head of Rosoboronexport, the Russian state-owned company responsible for arms exports.

The visit consolidated the strategic partnership and included discussions on the use of the ruble as the reference currency in bilateral contracts, symbolizing the definitive move away from the dollar.

In addition to military purchases, Vietnam and Russia reactivated joint projects in the oil and gas sector, replicating the cross-financing model that Moscow has been using to circumvent the Western blockade.

According to researcher Ian Storey, “the Russians have been very adept at finding alternative solutions, including defense exports through third countries.”

The strengthening of cooperation did not go unnoticed in Washington. Sources in the US Congress reported having received warnings about the growth of Vietnamese military acquisitions and the risk of loss of regional influence.

The reaction was hasty: Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth is expected to visit Vietnam in early November, in an attempt to contain the deterioration of the bilateral relationship.

Triangulation with Beijing and Pyongyang

Hanoi’s turn is not limited to Russia. Vietnamese leader To Lam visited Pyongyang and signed a defense cooperation agreement with Kim Jong-un, sealing the resumption of relations interrupted since the 2000s.

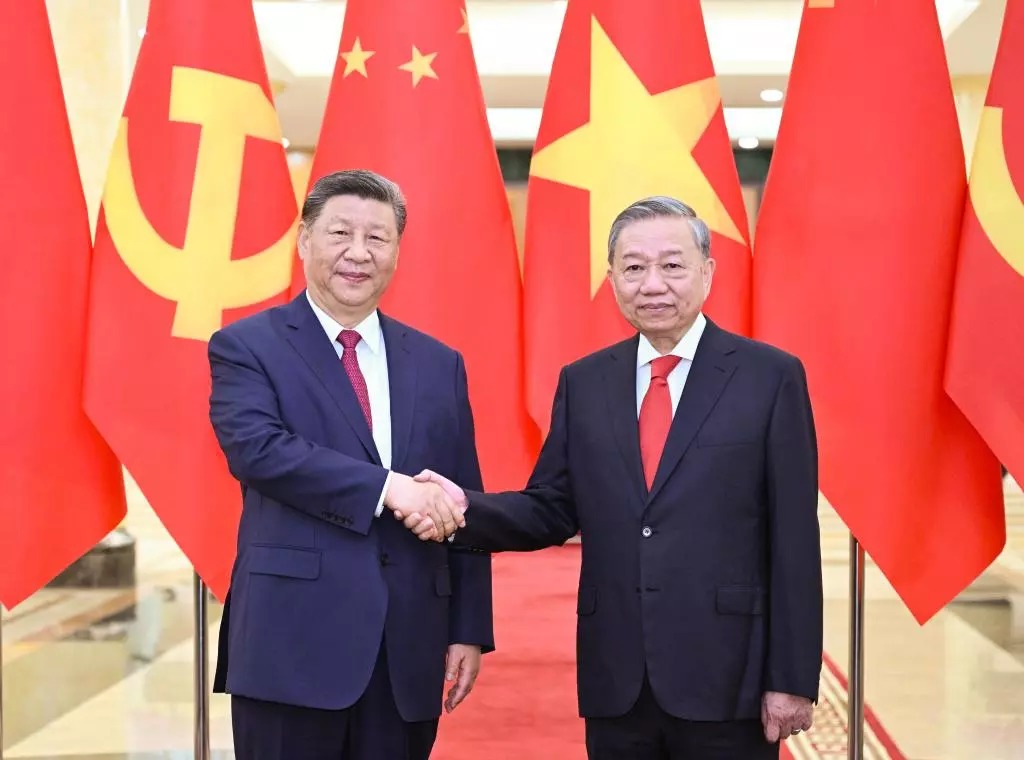

A few days later, Xi Jinping was received with honors in Hanoi, and the two countries announced the acceleration of three long-discussed cross-border railways.

The gesture has symbolic weight. China, once a military enemy of Vietnam, is once again a strategic partner in a context of multipolar reorganization. The rapprochement occurs in parallel with the advancement of industrial and energy integration projects under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative.

For Beijing, the strengthening of Hanoi means the consolidation of an Asian bloc less susceptible to US political fluctuations.

On a political level, local observers identify the resurgence of so-called “red nationalism” — a discourse that demands Vietnam’s total independence from any foreign power and revalues Ho Chi Minh’s revolutionary heritage.

This ideological renaissance is also expressed in foreign policy, which favors dialogue between socialist countries and the rejection of North American protectionism.

The joint presence of Li Qiang, Kim Jong-un, To Lam and Dmitri Medvedev in Pyongyang, on the anniversary of the Workers’ Party, crystallized the new geometry of power: a continental Asia that recognizes itself as autonomous and resists Washington’s tutelage.

In the words of Nguyen The Phuong, a Vietnamese researcher based in Australia, “the unpredictability of Trump’s policies has left Vietnam very skeptical about relations with the United States. It’s not just about trade, but the difficulty of reading his mind and actions.”

Between autonomy and multipolarity

Although Vietnam still depends heavily on the North American market — around a third of its exports go to the United States — the search for new alliances is interpreted by analysts as a survival reaction.

Trump’s oscillation between tariff threats and promises of “big deals” turned diplomacy into a reality show.

On the regional board, the changes have a direct impact on Japan, South Korea and Australia, Washington’s traditional partners who fear the loss of influence.

Hanoi, however, adopts a calculated stance: it diversifies suppliers, expands its drone production capacity and maintains open channels with all poles of power. The logic is the same that has guided Vietnamese foreign policy since the end of the Cold War — autonomy above all.

Ho Chi Minh’s phrase quoted at the end of the report New York Times sums up this spirit: “It all depends on the Americans. If they want to make war for 20 years, then we will make war for 20 years. If they want to make peace, we will make peace and invite them to tea afterwards.”

The revolutionary leader’s legacy continues to guide a country that has learned, from history, not to rely on fragile alliances.

The Vietnamese turn is, therefore, more than a diplomatic episode: it is a symptom of the new multipolar era. By losing Hanoi to the Moscow–Beijing–Pyongyang axis, the United States is witnessing the consolidation of its own Asian architecture, which is not subject to the logic of sanctions and tariffs.

For the region, the message is clear — security and development no longer depend on Washington’s mood, but on the ability of countries to assert their sovereignty.

Source: vermelho.org.br