Published 12/23/2025 16:39 | Edited 12/23/2025 16:57

United States President Donald Trump’s decision to impose a “total blockade” on oil tankers linked to Venezuela marked a new escalation in the relationship between the two countries. Caracas denounced the measure as a warmongering act and part of an intimidation strategy that includes military operations in the Caribbean, responsible for at least 95 deaths since September, according to data cited by North American parliamentarians. For the Venezuelan government, this is international piracy and an explicit attempt to control its natural resources.

Two recent podcast interviews analyzed the climate in Venezuela amid the US offensive. Both researcher Pablo Uchoa, interviewed by The Conversation Weeklyas well as journalist Rolando Segura, from Telesurdescribes in an interview with Eleonora Lucena (Tutameia), the risks for the Trump government are enormous in the face of prolonged pressure that has not created any crack in the Maduro government. Instead, it united 90% of Venezuelans against the threat of invasion, in addition to uniting neighboring governments that feel threatened by US neocolonialism.

“Only the most extremist sector of the Venezuelan opposition follows and speaks out in favor of aggression against Venezuela. In general, people who are not in the country, including the opposition member who went to Oslo to retrieve the million dollars they gave her for a supposed peace prize and, in her first statements, applauded this aggression against her own country”, says Segura. Today, Corina Machado’s opposition is frayed even among the country’s middle classes, especially while the economy has enjoyed a strong boost in recent years.

Roots of defense doctrine: from the 2002 coup to asymmetric warfare

Venezuelan defensive planning dates back to the coup attempt against Hugo Chávez, in 2002. According to Uchoa, the episode was decisive for the then president to start seeing security as something that goes beyond the military field. Inspired by the experiences of Vietnam and Iraq, Chávez consolidated the idea that an eventual war would not be “army against army”, but “people against an army”, betting on prolonged resistance and the wear and tear of the invader.

Created in 2008, the Bolivarian Militia became the axis of this strategy. With millions of members, according to official data, it integrates civilians into the territorial defense system, acting both in community surveillance and in preparation for a possible foreign occupation. For analysts, this is the so-called “second phase of the war”: after blockades and specific attacks, there would come widespread popular resistance, capable of making any invasion extremely costly.

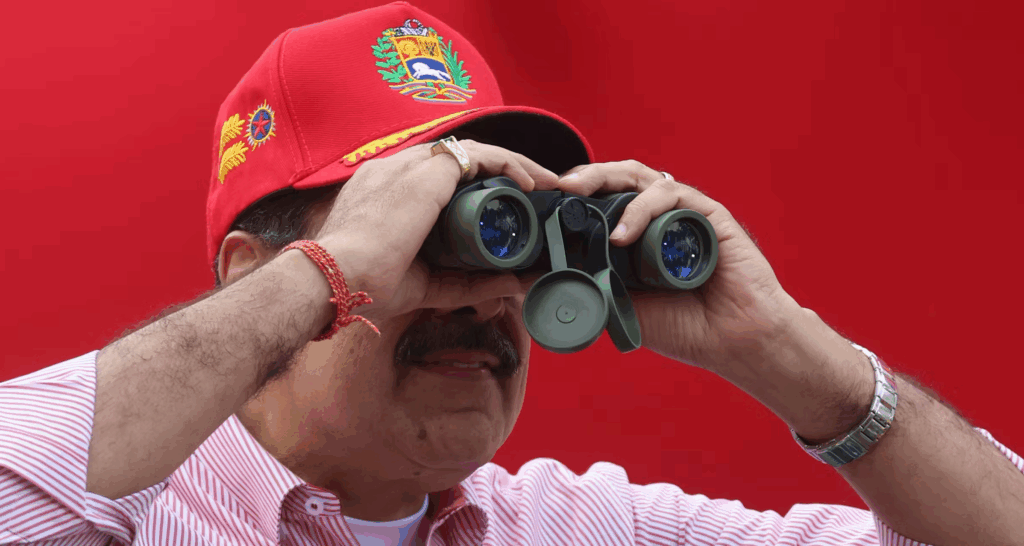

After Chávez’s death, Nicolás Maduro took office in a more adverse context. Severe economic sanctions, hyperinflation and US diplomatic offensives have deepened the government’s dependence on the Armed Forces, which currently maintains a vigorous civil-military partnership with the government. Even so, Maduro won elections contested by the opposition, but recognized by international observers, and reinforced his speech in defense of sovereignty in the face of what he classifies as an attempt at regime change sponsored by Washington.

One of the central effects of a conflict would be the deepening of the militarization of Venezuelan political life. Pablo Uchoa observes that, after the death of Hugo Chávez, Nicolás Maduro began to operate in a field of attacks on his electoral legitimacy, which led him to increasingly rely on the Armed Forces and popular support. According to him, it is in this context that the notion of “political-military direction of the revolution” emerges, something that was not central in the previous period.

An external conflict tends to reinforce this movement, as military crises function as classic mechanisms of forced cohesion of power. As the researcher himself summarizes, when analyzing leaders under pressure: “An autocrat loves a crisis. The crisis is the way in which the base is mobilized”, he says, referring both to centralizing governments such as Maduro’s and to Trump, with the difference between the eventual demobilization of the North American social bases. Trump voters feel betrayed by his broken promises not to involve the US in new international conflicts.

Faced with the first announcements of this intention to invade the country, in a massive way, Venezuelan men and women enlisted in the militias to defend their country. According to Segura, today, the Bolivarian Forces, commanded by the great patriotic pole — which is not only the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, the political organization that leads the country —, there is another great confluence of youth organizations, women’s organizations, peasants, workers, who follow this entire process, who support the constitutional order in Venezuela, and are very organized to face not only this intention of aggression against the country, but to face the challenges that Venezuela has been facing during the last period.

In practice, in Uchoa’s opinion, this could also mean greater social control, repression of internal opponents and reduced space for political mediation, under the argument of national defense.

From a social point of view, the interviews show that preparation for war already impacts the daily lives of communities. The territorial defense strategy described by Uchoa involves dividing neighborhoods into areas monitored by community groups, forming a dense surveillance network.

He explains: “You would have a social fabric that would be very difficult to penetrate, because anyone seen as hostile could be attacked.”

This model, thought of as resistance to a foreign invasion, has ambiguous effects. On the one hand, it strengthens the idea of popular sovereignty and direct participation in the country’s defense. On the other hand, it can encourage permanent distrust, complaints between neighbors and a climate of fear, reinforced by tools such as surveillance applications and security operations which, according to the interviewee himself, became known as “ringing on the door in the middle of the night”.

Daily life, popular support and rejection of war

Despite the threats, Caracas maintains a climate of relative normality. Journalist Rolando Segura, from Telesur, describes in an interview with Eleonora Lucena (Tutaméia) a capital in daily routine, although attentive to external pressure. Recent surveys indicate that more than 90% of the Venezuelan population rejects a foreign invasion, a position shared even by sectors of the opposition. In the USA itself, surveys show a majority against a war against Venezuela.

For analysts and Venezuelan authorities, the US offensive reflects the attempt to reaffirm hegemony over a region rich in oil, minerals and water, at a time of advancement in Latin America’s relations with China, Russia and Iran. A military intervention, they warn, could destabilize the entire continent, increasing migratory flows and conflicts. In this scenario, Caracas is betting that the two-decade preparation will work as a deterrent and turn any aggression into a “new Vietnam” for Washington.

The interviews also make it clear that a conflict would not just be military, but profoundly economic and social. Rolando Segura highlights that, despite the apparent normality on the streets, external pressure is already beginning to be felt: “Life continues in its daily routine, but tension is beginning to be felt, especially from an economic point of view, when buying Christmas gifts.”

Sanctions, naval blockades and instability affect inflation, supply and income, directly penalizing the civilian population. An armed conflict would magnify these effects, worsening inequalities and making living conditions even more precarious, especially in popular sectors.

Mass migration and regional destabilization

One of the most serious consequences highlighted in the interviews is the migratory impact. Segura warns that an invasion could cause large-scale population displacement:

“Analysts agree that this would result in the destabilization of the entire region.”

Venezuelan migration already exerts political pressure on neighboring countries and, according to Uchoa, is instrumentalized by conservative forces in Latin America:

“Venezuelans in the region push the political debate to the right, and this makes it difficult to reach a common position against an invasion.”

An armed conflict, therefore, would not only increase migratory flows, but would also reorganize the regional political board, strengthening security, xenophobic and authoritarian discourses.

Politically, interviews suggest that a war against Venezuela would deepen ideological polarization in Latin America. The country already functions as a symbol used by both the right and the left, which makes unified diplomatic responses difficult. Furthermore, Segura points out the discredit of international organizations in the face of the military escalation: “International organizations were not even able to stop the genocide in Palestine. Little can be expected of them in situations like this.”

This institutional void reinforces the perception that conflicts are now resolved by force, not by international law, which further weakens the multilateral order.

Sovereignty as a red line

Between fiery speeches, military preparation and popular mobilization, Venezuela reaffirms that its defense does not depend on allied powers, but on the population itself. For the government and its supporters, the ongoing conflict is not just national, but a symbolic clash against the explicit return of colonial pretensions in Latin America. Segura demonstrates that it is difficult for neighbors to understand Venezuelans’ historical pride in their sovereignty. These people, according to him, do not intend to count on Russian or Chinese military aid to defend themselves. “Venezuela is defended by Venezuelans and Venezuelans.”

Finally, the interviews indicate that an armed conflict would tend to radicalize internal political identities. Segura highlights that, even among opponents of the government, there is widespread rejection of foreign aggression: “More than 90% of the population rejects the intentions of invading the country.”

This suggests that an invasion could strengthen nationalist and resistance sentiments, but also merge criticism of the government with betrayal of the homeland, reducing political pluralism. The defense of sovereignty becomes the central axis of social life, with high costs for democratic diversity.

As Uchoa summarizes, regime change may seem simple “on paper”, but sustaining a country under occupation or prolonged war would be the real challenge — with human and political costs that fall, above all, on the civilian population.

Source: vermelho.org.br