Frasso was still a newbie at El Nacional, one of Venezuela’s biggest dailies at the time, when he was sent to downtown Caracas on Feb. 27, 1989, to cover what they called “some protests.” For the young photojournalist from the small town of Santa Ana, in the interior of the state of Anzoátegui, who had started out in photography taking pictures of graduations and funerals, working for a major newspaper in the capital was, until then, the highlight of his career. .

What Frasso didn’t know is that, when he arrived at the headquarters of the Fire Department on Avenida Bolívar and recorded the first fires on that morning of the 27th with his camera, he was beginning to cover one of the biggest social uprisings in the history of Venezuela, which would have decisive in the country’s political future and in its own journalistic trajectory: Caracazo, which turns 34 this Monday (27).

Francisco Solórzano, nicknamed Frasso by his first writing colleagues, was one of the main photographers to record the brutal violence with which the Venezuelan State repressed the protests that took over Caracas and other regions of the country in the last days of February 1989.

::What’s happening in Venezuela::

“Seeing a 16-year-old boy being murdered before your eyes with a shot in the stomach, that’s not just anything,” he tells the Brazil in factmaking clear the burden and glory of having participated in that coverage.

Venezuela began 1989 facing a serious economic crisis, with factors typical of the instability of countries dependent on oil income: skyrocketing inflation, exchange rate devaluation, product shortages and recession. At this juncture, the social-democrat Carlos Andrés Pérez, who had already been president between 1974 and 1979, had just assumed his second term with the promise of recovering the good times financed by the rise in oil prices that marked his first government and restore the so-called “Saudi Venezuela”.

The nostalgic appeal to voters would prove false when Pérez announced, during the first days of his new term, a package of neoliberal economic adjustments agreed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), under the justification of reducing the State and giving more space to the market. to overcome the crisis.

The shock was immediately felt by the poorest and middle classes. Increases in almost all basic services such as telephony, water and electricity, public transport tariffs, fuel, and the end of price controls on some basic items were the main measures that triggered the popular revolt.

On the morning of February 27, workers using the bus terminal in Guatire, a satellite city of Caracas, revolted against yet another increase in bus fares and began to protest. Pickets were set up in the streets and the first reports of fires and looting began to make the news. It didn’t take long for Guatire’s example to spread to the capital and other regions of the country.

“It was a spontaneous explosion”, says Frasso. “This was not organized by any political party, it was the reaction of a people full of discontent with the policies at that time,” he says.

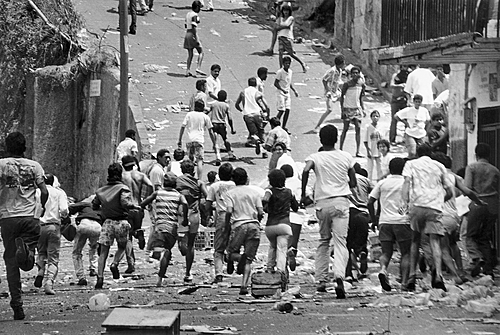

19 de Abril Community, in Petare, east of Caracas [foto cedida pelo autor] / Francisco ‘Frasso’ Solórzano

The government reacted quickly and in the worst possible way, even calling on the Armed Forces to contain the demonstrators. From the night of the 27th to the morning of the 28th, Caracas was taken over by security forces who began to open fire on the popular mass that came out to protest.

The official version speaks of 276 dead, but the number is widely refuted by human rights organizations, social movements and by almost everyone who lived through the acts of repression. According to Committee of Relatives of Victims of the Caracazo (COFAVIC), an NGO born after the events of February 27, 1989, state violence against protests may have left up to 3,000 dead and missing.

Although former president Carlos Andrés Pérez was never held legally responsible for the deaths, pressure from sectors of civil society and Parliament was enormous and ended up making his government unsustainable. The fatal blow would come in 1992, when then-unknown Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez led a military rebellion to try to overthrow Pérez. The movement failed, but gained wide popular support and put even more pressure on Carlos Andrés, who ended up being removed from office in an impeachment process in 1993.

::Everybody has a story with Chávez: Venezuelans celebrate 31st anniversary of 4F rebellion::

The Caracazo was the trigger for a political process that put an end to the period that passed into the history of Venezuela as the 4th Republic, which began in 1958 with a pact between the main parties: Democratic Action and the Independent Electoral Political Organization Committee (Copei). In the 1998 presidential elections, Chávez knew how to organize the popular support he had won in his attempt at rebellion and the existing discontent with the traditional parties, extremely worn down by the economic crisis and the history of repression during the Caracazo.

Frasso’s photos of the February 1989 revolt are part of this historical process and expose human rights violations committed by state repression forces. His work covering Caracazo earned him the King of Spain Photography Award in 1989 and, in addition, served as evidence in the process that relatives of victims of repression filed against the State at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, from which they obtained a favorable decision in 1999.

Frasso inaugurated an exhibition of his works last Saturday (25) / Lucas Estanislau

Last Saturday (25), Frasso attended the opening of an exhibition in Caracas about his work. His 68 years of age and fragile state of health did not prevent the photographer from walking through the corridors of the gallery explaining the works and giving details about each of his professional phases. Frasso has photographed the work of Venezuelan peasant women, natural landscapes, Latin American intellectuals and was even the official photographer of Chávez’s first campaign, in 1998.

“But I always remember the 27th of February and those days that followed”, confesses the reporter, who spoke with the Brazil in fact about covering the uprising that changed his life and that of a country.

Check the interview in full:

Brasil de Fato: How did coverage begin on February 27, 1989? When was the first time you heard about the protests?

Frasso: The day started out like a normal work day. The government had already announced the increase in gasoline prices, the freezing of wages, all of this in the midst of an economy that only made the people poorer. On the afternoon of the 27th, we were sent to cover events in downtown Caracas, on Avenida Bolívar. I was responsible for going to the Caracas Fire Department headquarters and witnessed the fire of the first bus in the city. Many people who lived in Guatire and came to Caracas to work were unable to return home because of the marches that were also taking place there. It was a very tough day. Around midday a curfew was declared and this meant that on the night of the 27th to the 28th another serious action took place, because the government was taken by surprise and began to ask that soldiers who were in the interior of the country to come to Caracas with weapons. Some of these soldiers had less than two months in the barracks. These were the ones who, with presidential orders and those of the then Minister of Defense, Ítalo del Valle Alliegro, shot at people who were protesting in the streets. In the early hours of the morning of the 28th, we began to see the first deaths, especially in the “slums” [bairros pobres] from Caracas. So, that day, they sent me to the 19 de Abril community in Petare and that’s where I took the well-known photos: the man on the motorbike, the young people murdered in the hills who were being carried by other comrades, all of this I began to see there, in Petare on that day.

‘The man on the bike’, victim of repression [foto cedida pelo autor] / Francisco ‘Frasso’ Solórzano

But until then you were covering protests. Did you ever think those acts would have the impact they did?

On the 28th, when there was already a curfew, I already thought that I had to record the events and keep the images well guarded because it wasn’t a coup d’état, it was the people in the streets trying to liquidate a representative democracy and replace it with a participatory democracy. They asked for an inclusion process, they asked that the people also be able to govern and have actions. This started with the Caracazo explosion. I never imagined the magnitude and consequences of this event. Even today, 34 years after the events, we still think: ‘my god, we could never have imagined this’. Because an explosion is the product of that permanent heating that exists within the masses and that existed at the time of Caracazo.

What did you feel behind the camera?

A mix of anger and sadness. Because seeing a 16-year-old boy killed before his eyes with a shot in the stomach, that’s not something. Seeing mothers crying because their children were murdered at the doors of their homes, that’s not just anything. That was the order, murder. I still believe there is justice to be done in the events of February 27th. I was a witness at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. There, with my photographs and my testimony, it was possible to sue the State. In 2003, during Chávez’s first government, compensation was approved for a group of relatives of Caracazo victims and we feel that we are part of this achievement. At that time, I was a deputy and member of the Finance Committee of the Parliament and I was able to participate in the discussions and press for the approval of the compensation that was handed over to these families, who sought justice not only for the death of their children, but also for the massacre of a country . In addition, they asked for the identification of the bodies that were still in mass graves in the Caracas cemetery, in that place known as ‘La Peste’, which I myself visited during those days in Caracazo.

But wasn’t “La Peste” a clandestine mass grave? How did you manage to get there during the repression?

We followed a truckload of coffins down the lane. I even have a photo of it. After chasing this truck, I entered the cemetery and passed the place where the dead of the Jewish community are buried. Going a little further on and at the foot of a hill we saw that there were some holes that had just been filled in and a meter and a half away from that point was this common grave, ‘La Peste’.

‘We followed a truck’, says Frasso [foto cedida pelo autor] / Francisco ‘Frasso’ Solórzano

Did you suffer any kind of retaliation after your Caracazo photos gained so much notoriety?

There was censorship from the beginning, but what was stronger was the self-censorship of some editors who, in the days following Caracazo, asked us not to take pictures of corpses and repression, but of normal situations, of people sweeping the streets, etc. About this there is another interesting story that took place on the anniversary of the newspaper El Meridiano. I went to the event to take some pictures and there was the then president Carlos Andrés Pérez with Pepe Consuegra, who was one of his press agents at the time. Consuegra introduces me to Pérez and says: ‘President, here is the journalist who won the King of Spain Award’. ‘And why did you win?’, Carlos Andrés asked me, to which I replied: ‘for your dead on February 27th, president’. This caused me many problems, including I was banned for a long time from working at the Miraflores Palace [sede do Poder Executivo venezuelano].

Do you think that your work accelerated the end of the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez and the 4th Republic?

I think the most important thing is that my work has served and continues to serve to maintain the collective memory of Venezuelans, to keep the people oriented and aware of these events. Today it is possible to say that these photographs became a symbol of the struggles that later took place in the country. I always remember the 27th of February and the days that followed and I continue to believe that any government that turns its back on the people will be doomed to failure.

Editing: Thales Schmidt

Source: www.brasildefato.com.br