Published 01/06/2024 16:56 | Edited 06/01/2024 17:09

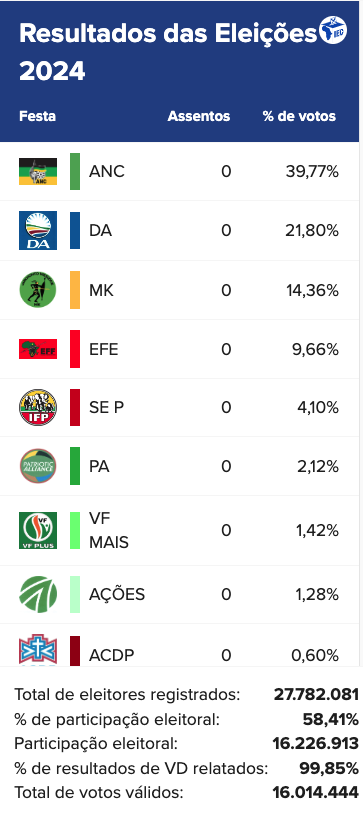

For the first time since the end of apartheid, the African National Congress (ANC) has lost its majority in South African elections, marking a major setback for the party that led the country’s liberation from white minority rule. The ANC, in power since 1994, obtained around 40% of the votes (39.77% after 99.85% of ballots counted), a significant drop compared to previous elections. A loss of 17% of votes compared to the 2019 election.

With the loss of its majority, the ANC began negotiations behind closed doors with other parties to try to form a government coalition, something unprecedented in the party’s history. However, analysts indicate that the ANC’s losses and pressure from potential alliance partners have cast a cloud over the future of President Cyril Ramaphosa, who the party had hoped would usher in a new term.

The main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (AD), obtained 21% of the vote. Former president Jacob Zuma’s uMKhonto we Sizwe (MK) party stood out as the big surprise of the elections, winning almost 15% of the national vote and 45% of the vote in KwaZulu Natal, Zuma’s province. This performance places MK in a critical position in determining who will form the next government, and confirms itself as the party that devastated the ANC’s electoral base.

Read also: With 20% of ballots counted in South Africa, CNA does not reach 50%

Election in South Africa could reveal loss of hegemony of the African National Congress

Pressure on Ramaphosa

MK, whose leadership includes many politicians with ANC roots, has ruled out any deal with the ruling party unless Ramaphosa is removed. After leading the ANC to its worst electoral performance, Ramaphosa faces intense pressure to step aside. Despite this, his popularity is even greater than that of his party, especially after polishing his image as a statesman from the Global South, which creates a dilemma for the ANC.

The resentment goes back to the period when, assuming the role of party leader and president, Ramaphosa created a commission of inquiry to investigate Zuma and referred to his former boss’s presidency as years of corruption and waste. Zuma, in public statements, has responded numerous times to the president and the ANC and feels the need to be cleared of the accusations.

Analysts estimate that the MK is enhancing its pass by refusing an automatic coalition, to guarantee more concessions from the ANC. A coalition between the CNA and the AD would be even more disastrous for a left-wing party like MK, which criticizes the current government for its centrist, rather than left-wing aspects.

DA critics have accused it of abandoning the interests of the country’s white minority, and the party has been an outspoken critic of the ANC and Ramaphosa. Before the elections, he promised to “rescue South Africa from the ANC” and promised never to form a coalition government with it.

South Africa faces a scenario of deteriorating public infrastructure, social inequalities and increasing crime. The country has the highest unemployment in the world, at 33%, and youth unemployment is 45%. Continuous electricity blackouts harm the economy.

Ramaphosa and other ANC leaders face corruption scandals, with the president having faced a vote of no confidence over allegations of misconduct. The ANC’s decline is also a result of the rise of Zuma’s MK, which has a loyal support base in KwaZulu Natal. However, the wear and tear of the ANC is natural after 30 years of government, despite so many advances made in social areas. The youth who do not appreciate the importance of the party for the end of apartheid, however, want more and faster.

Coalition Options

If the ANC and MK unite, they would have a clear majority in parliament. However, analysts point out that this will be difficult to achieve. Alternatively, a coalition with the AD could offer a more stable governing alliance. Despite the profound differences, a CNA-DA combination could increase investor confidence in the country’s economy. The country would be aligned with market values and hegemonic neoliberalism in the world today.

Another option would be a government of national unity, where all parties with more than 10% of the vote would receive cabinet portfolios, similar to the government that Nelson Mandela led after coming to power in 1994. This hypothesis, however, creates a monster of seven heads with each party wanting to show their claws in government.

Analysts question whether Ramaphosa’s removal will help to recover the party, which, due to its importance and greatness, even with the electoral setback, means that its internal disputes are placed above certain national issues. The least of South Africa’s (and the ANC’s) problems at the moment is Ramaphosa.

Source: vermelho.org.br