Published 01/27/2024 10:30 | Edited 01/27/2024 10:33

In July 1921, three years before his death, Lenin wrote to the Soviet writer Maksim Gorky: “I am so tired that I cannot do anything.” Still, Lenin participated in up to 40 meetings and committees a day and received dozens of people.

“From the meetings of the Council of People’s Commissars”, recalled his sister Maria Uliánova, “Vladimir Ilyich arrived at around 2 o’clock at night, completely exhausted, pale, sometimes he couldn’t even speak or eat, he used to pour himself a glass of milk hot and drank it walking around the kitchen where we used to have dinner.”

Professor Livéri Darkchevitch, who examined Lenin in March 1922, noted “an enormous number of extremely severe neurasthenic manifestations which completely deprived him of the possibility of working as a [o fazia] before” and “a series of obsessions that scare the patient a lot”. “That won’t lead to madness, right?”, Lenin asked the professor.

In April 1922, Lenin began to feel so ill that doctors suggested he might have been poisoned by lead bullets that remained in his body after the assassination attempt on August 30, 1918. According to academic and surgeon Yuri Lopukhin , “the decision [de retirar balas do corpo] is very controversial and doubtful, taking into account that during these four years since the assassination attempt, the bullets were already lodged and, as Professor Vladímir Rozanov believed, their removal “will do more harm than good”.

On April 23, 1922, German surgeon Borchardt removed a bullet from Lenin’s body, and on April 27, the Soviet leader had already returned to meetings. He continued to work actively for another month, until on May 25 he suffered his first stroke at his home in Gorky, near Moscow. The stroke led to the loss of speech, he was sometimes unable to read or write, and he had little control of his right hand.

On May 29, the council of doctors, which included the participation of the great neurologist Grigóri Rossolimo and the people’s commissar (minister) for Health, Semachko, admitted that the disease was not clear. It was assumed to be atherosclerosis, but doctors were surprised to see that Lenin’s intellect remained completely intact.

In the summer of 1922, Lenin’s health began to show signs of improvement. On June 16, he began to get out of bed and, as nurse Petrácheva said, the Soviet leader “even danced with me”. However, pathological manifestations continued throughout the summer; Lenin sometimes lost his balance and, on August 4, he had a spasm with loss of speech following the injection of arsenic with which he was treated.

Five months after his stroke, Lenin returned to Moscow. Teachers believed he was fully recovered, but he admitted: “Physically I feel fine, but I no longer have the same freshness of thought. To put it in professional language, I lost the ability to work for long periods.”

In October and November 1922, Lenin participated in several meetings of the Council of People’s Commissars and spoke at congresses and conventions. His strength came to an end on December 7, when he left for Gorky. On December 12, Lenin returned to Moscow, where he suffered convulsions and a second stroke, after which the right side of his body became paralyzed.

On December 24, 1922, Stalin called a meeting with the participation of the leaders of the USSR: Lev Kamenev, Nikolai Bukharin and Lenin’s doctors. They decided to protect him from news about political life, “so as not to provide material for reflection and concern”. He was also banned from receiving visitors.

Despite this, Lenin continued to dictate notes and letters until March 9, 1923, when he suffered a third stroke. He lost his ability to speak again and never returned to work. In the summer of 1923, under the supervision of his wife, he was forced to relearn how to walk, pick up objects and speak.

Krúpskaia wrote: “He already walks with assistance and independently, leaning on the handrail, going up and down stairs. […] He is in a very good mood and now he realizes that he is recovering.” From October 18th to 19th, Lenin was in Moscow for the last time; from there he returned to his dacha in Gorky.

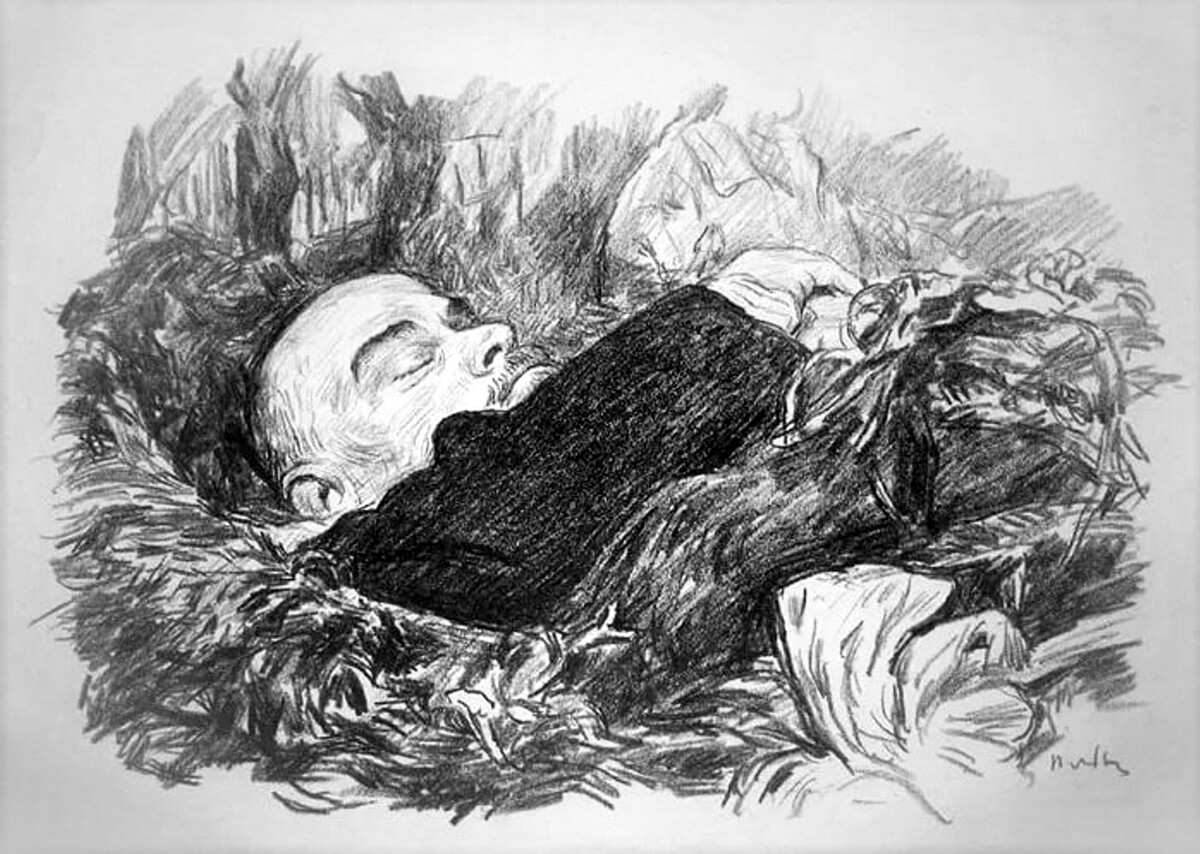

Vladimir Lenin died in Gorky on the night of January 21, 1924, at 6:50 pm. He was 53 years old. An autopsy of the body was carried out the next day in the morning. Historians still do not know why the body was not taken for autopsy to Moscow, where the best medical institutes were located.

There are two versions of the main cause of Lenin’s death: cerebral atherosclerosis and (complications) of syphilis. Today, 100 years after his death, there is still no consensus on this issue. Academic Yuri Lopukhin suggests that the true cause of Lenin’s illness and death was insufficient blood pumping to the brain caused by his injury in 1918.

A significant part of the documents on Lenin’s death and illness remain secret to this day at the request of his niece Olga Uliánova (1922-2011). However, the secrecy now expires in 2024.

Originally published on Russia Beyond Brasil

Source: vermelho.org.br