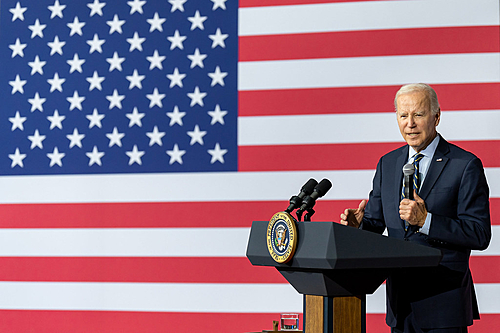

The government of US President Joe Biden has received yet another request to ease sanctions on Venezuela. This time, the demand came from his own party, after Democratic congressmen asked for a review of the blockade implemented against the South American country by previous governments.

According to the newspaper Washington Postdeputies and senators from the Democratic Party sent a letter to Biden arguing that economic sanctions have stimulated the flow of Venezuelans to the US.

“Experts broadly agree that US extraterritorial sanctions – expanded to unprecedented levels by its predecessor [Donald Trump] – are a predominant contributing factor to the current rise in migration,” reads the letter quoted by the newspaper.

::What’s happening in Venezuela::

Also according to the American newspaper, the parliamentarians asked the president to act “quickly to eliminate the failed and indiscriminate economic sanctions that were imposed by the previous government.”

The pressure comes a day before the repeal of the so-called Title 42, a measure instituted by former President Donald Trump who, under the pretext of containing the spread of covid-19, implemented a policy of rapid deportation that even prevented asylum requests.

With the end of the sanitary prerogative, Washington fears an increase in the migratory flow, since the authorities will be forced to accept requests for refuge and asylum that, while not resolved by the Justice, force migrants to wait in state facilities in border cities.

::Without US sanctions relief, Venezuela expands partnerships with Russia and China::

Border regions such as the city of El Paso, in the State of Texas, are experiencing emergency situations, as state and non-governmental entities to aid migrants are unable to assist the thousands of people who are waiting for the end of Title 42 to try to stay in the country. country.

sanctions as a weapon

The US has been imposing sanctions on Venezuela since 2014, but it was after 2017 that these measures began to attack strategic sectors of the country’s economy. First, a financial blockade was instituted by Trump, which practically froze the Venezuelan foreign debt and prevented the government of Nicolás Maduro from negotiating bonds and loans on the international market.

In 2019, the target was PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company, which is mainly responsible for the country’s dollar inflows. The sanctions imposed by the White House suffocated the industry, which produced about 3 million barrels a day in 2012 and started to produce only 200 thousand barrels a day in 2020.

::Without Guaidó, what is left for the US and Venezuela to resume relations?::

The crisis in the energy sector was one of the main factors that contributed to a reduction of more than 70% in the country’s GDP in the last 10 years. With the lack of dollars from oil income, a serious exchange rate crisis gripped the country and threw Venezuela into an inflationary spiral that reduced wages and spurred migratory waves of millions of Venezuelans fleeing the crisis. According to UN data, more than 5 million people have left the country since 2014.

One of the main destinations for migration was neighboring Colombia, the country that received the most Venezuelans in recent years. Unlike his right-wing predecessor Iván Duque, the government of President Gustavo Petro has already warned of the humanitarian risks of the high flow of migrants in the country and has become one of the main voices against sanctions in South America.

On his visit to Washington in April, Petro met with Biden and urged the president to lift the blockade against Venezuela. In addition, the Colombian president even convened a conference in Bogotá that brought together 20 countries, including the US, to discuss the end of sanctions.

::Businessmen and opposition politicians ask the US to end sanctions against Venezuela::

In the private sector, there are also agents interested in easing the blockade, such as the giant Chevron, the Italian Eni and the Spanish Repsol, all in the energy sector. With the fuel demand crisis generated by the war in Ukraine, companies began to consider a return to activities in Venezuelan territory, but sanctions prevent most operations.

At the end of last year, Washington allowed Chevron to return to Venezuela to reactivate the four mixed plants that the company operates together with the state-owned PDVSA, although the conditions are still very limited in financial terms.

The Europeans Eni and Repsol, on the other hand, obtained a US license that allowed the resumption of negotiations with Venezuela, but that prevented any type of payment to PDVSA for oil products. The idea was that Caracas could sell barrels and derivatives to companies in exchange for amortization of debt installments that Venezuela owes. The scheme was rejected by the Venezuelans.

Editing: Rodrigo Durão Coelho

Source: www.brasildefato.com.br