Published 01/29/2026 17:09 | Edited 01/29/2026 17:39

Russia and China announced that they will publish, in 2026, the complete correspondence between Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, in one of the largest documentary declassification projects in recent decades. There will be around 420 letters, telegrams and notes exchanged between 1943 and 1953, more than 250 of them unpublished for historians.

The initiative, conducted in cooperation between the Russian federal archives (Rosarkhiv) and Chinese institutions, breaks decades of secrecy and occurs at a time of strong geopolitical reconfiguration, marked by the deepening of the Moscow-Beijing axis in the face of pressure from the United States and Western allies.

Behind the scenes of the communist victory in China

Much of the correspondence dates back to the decisive period at the end of the Chinese Civil War and the first years of the People’s Republic of China, proclaimed in 1949. The documents reveal Stalin acting as Mao’s strategic advisor, discussing everything from military tactics to state organization, logistics, epidemics, food supply, railways and airlines.

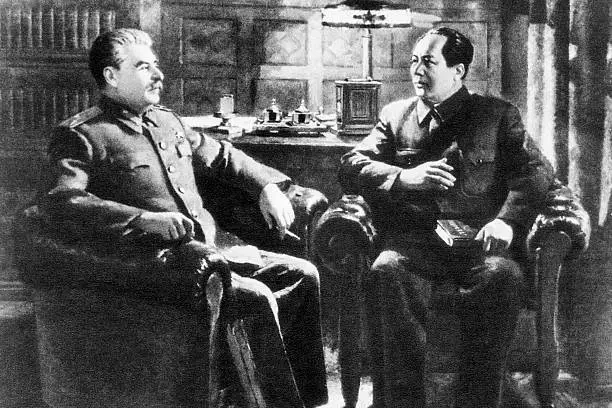

Far from simple diplomatic formalities, the letters indicate an intense dialogue between two leaders who shaped the post-war socialist world. Stalin, who used the pseudonym “Comrade Filippov” for security reasons, offered practical recommendations and, in some cases, direct military aid, such as the provision of anti-aircraft weapons.

The Soviet leader offered practical recommendations. “The project copies the Soviet model of an administrative-planning center and is very complex. It needs to be simplified and reduced,” he wrote to Mao about the creation of government bodies. And in one of his messages, he directly proposed: “If you are not afraid to accept Russian-style anti-aircraft guns and cannons, we can provide them.”

Alliance and pragmatism

Despite the later image of monolithic unity, the correspondence must expose a relationship marked by mutual caution. Stalin maintained reservations since 1930, even after the Chinese communist victory. Mao, in turn, sought Soviet support without giving up strategic autonomy. But the tone of the correspondence is surprising: no pressure or imposition, just friendly advice and mutual respect.

The Korean War, which began in 1950, brought the two countries closer together, consolidating the alliance formalized in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance. Still, the documents suggest that cooperation coexisted with latent tensions, which would come to the surface after Stalin’s death in 1953, and culminate in the Sino-Soviet split in the following decades.

Archives as a political instrument

The head of Rosarkhiv, Andrei Artizov, made it clear that Russia’s archival cooperation policy today is organized around “friendly” countries, citing China, India, Vietnam and other strategic partners. In this context, the opening of the archives is not only an academic gesture, but also a political one.

The coordinated release of these documents can function as a tool of historical diplomacy: it reinforces the narrative of a deep partnership between Moscow and Beijing, signals strategic alignment in the present and offers Russia symbolic capital in future negotiations, including with the West.

Impact on history and the present

For researchers, the publication promises to redefine the understanding of the formation of the Asian socialist bloc and the Soviet role in consolidating the Chinese regime. For international politics, the gesture carries another message: history, when declassified at the right time, can be used as political and diplomatic language.

By opening the archives of Stalin and Mao now, Russia and China are not only revisiting the past — they are reactivating it as a vector element in the dispute of narratives and the construction of alliances in a world once again marked by systemic rivalries.

Watch video about the archive of correspondence between Stalin and Mao

In the video, the correspondent of the Zvezda TV channel gets in touch with the originals in Moscow. Correspondence was carried out via encrypted telegrams, transmitted by trusted individuals: Mao’s Soviet advisors, delivery services, and special representatives. Many documents were handwritten by Stalin or Vyacheslav Molotov himself, with edits by both leaders — a clear indication of direct intervention in the text. It was not a question of dry bureaucracy, but of a lively dialogue between two architects of the socialist world.

Source: vermelho.org.br