Published 01/10/2026 10:54 | Edited 01/11/2026 14:26

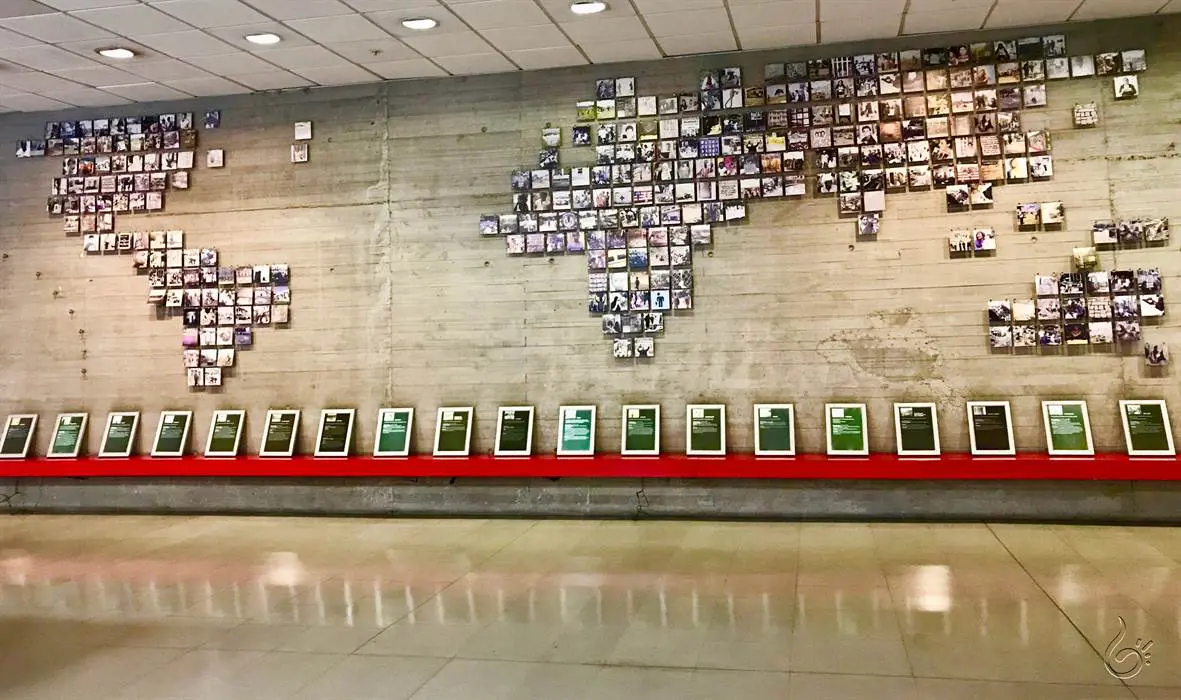

Passing through Chile on special coverage for the Red Portalwe visited the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, in Santiago. Today, the space is one of the main references in Latin America in preserving the memory of violations committed during the Chilean civil-military dictatorship and in promoting a democratic culture based on human rights.

We were welcomed by the museum’s executive director, Maria Fernanda García, who gave us a long and careful interview about the role of memory, art and education in human rights in a world crossed by narrative disputes, denialism and new forms of state violence.

The conversation covered his personal trajectory, the political and pedagogical meaning of the museum, the dialogue with young people, the protagonism of women, Latin American connections and the contemporary challenges of democracy. Below, we publish excerpts from the interview, maintaining the central content of the speeches.

To begin with, could you introduce yourself and tell us a little about your journey until you became the director of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights?

I’m Maria Fernanda García, executive director of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights. My initial training is in the performing arts. I was an actress, then I studied Cultural Administration and did part of my training in Spain, at the Complutense University of Madrid, where I lived for five years. At the same time, I am also a flamenco teacher, a practice that runs throughout my cultural life. My trajectory has always combined art, cultural management and public policies. I worked in the management of cultural centers, foundations and museums, always focusing on cultural promotion, human rights and, especially, valuing the perspective of women. Three years ago I took over the management of the museum through a public competition, which I consider very important from an institutional and democratic point of view.

The museum was born based on the recommendations of the Truth Commissions. What is the role of the museum in Chilean society today?

The museum was created as a form of symbolic reparation by the Chilean State in the face of the massive human rights violations committed during the dictatorship. He emerges to respond to the victims, their families, but also to a deeply fractured country. From the beginning, the museum was not just thought of as a space to remember the past, but as a space for ongoing education in human rights. Memory is not something fixed, it is reconstructed collectively. Therefore, the museum works so that Chilean society can understand what happened, reflect on it and make ethical commitments for the present and the future.

In a context of narrative disputes and denialism, how does the museum deal with these tensions?

We are experiencing a true war of narratives in the world. There will always be people who will try to relativize or deny the facts, even in the face of extensive documentation and historical evidence. Our role is to work with rigor, documentation, archives and testimonies. Here everything is documented. This does not prevent denialist speeches from existing, just as there are people who believe that the Earth is flat despite all the scientific evidence. But the museum positions itself clearly: there are facts, there are documents, there are victims, there are responsibilities of the State. Human rights education is fundamental precisely to confront these attempts to distort history.

Art occupies a central place in the museum. Why this choice?

Because art is a language that reaches where rational discourse often cannot reach. It enters through the unconscious, through affection, through the heart. Art allows us to approach extremely difficult topics in a way that generates empathy, reflection and action. Theater, music and visual arts allow us to show horrors without trivializing them, provoking questions, emotions and personal learning processes. Art does not replace information, but deepens and humanizes it.

The museum has many projects aimed at children and youth. How to dialogue with generations that did not experience the dictatorship?

Each age requires a different language. With young children, we work on values such as respect, collective care, solidarity. We are not talking directly about torture, but about coexistence, empathy, rights. With young people, we address more complex topics, such as forced disappearance, migration, exile, state violence. Many young people connect with these experiences because they are currently experiencing displacement, forced migration, and family disruptions. Memory dialogues with the present.

Projects with rap, electronic music, graffiti and other urban languages have brought new audiences closer to the museum. What impact does this generate?

It’s transformative. Many young people had never entered a museum because they saw it as an elitist, distant, formal space. When the museum opens up to these languages, they feel welcomed. We have programs in which young artists spend months in training, creating works based on memory, democracy and respect. The artistic and personal growth is impressive. Many today are recording albums, producing works, taking memories to other spaces.

The gender perspective is very present in the museum. Why?

Because for a long time women appeared only as secondary victims of history. Here we work to show women as protagonists of resistance, political organization, defense of life and democracy. Incorporating a gender perspective is fundamental to understanding the full dimension of violations and struggles. Women were and are at the forefront of defending human rights.

Also read: Chile Stadium: memory, resistance and the permanent fight against oblivion

How does the museum dialogue with other experiences in Latin America?

Permanently. Latin American dictatorships share methods, alliances and social impacts. We work with exhibitions and exchanges that cover Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, among other countries. Memory is not just national. She is continental. Thinking about Latin America means thinking about intersecting histories of violence, but also of resistance and solidarity.

In a world marked by wars and humanitarian crises, what is the role of memory spaces today?

Memory spaces are fundamental to strengthening democracy. They do not exist for eternal mourning, but for conscious action. It is not necessary to be in a government to defend human rights. Each person can and should commit. Memory reminds us that nothing is guaranteed forever. Rights need to be defended every day.

What message would you leave to Latin American youth?

Let them not lose hope. We live in difficult times, but also full of possibilities. Democracy is built with participation, organization, solidarity and ethical commitment. Human rights must be the minimum floor of our coexistence. From there, we can build more just, egalitarian and humane societies.

A memory that lives on

At the end of the visit, it became clear that the Museum of Memory and Human Rights is not just a space of remembrance, but an active territory of symbolic dispute, political education and production of meaning for the present. In times of authoritarian threats and historical erasures, spaces like this continue to be fundamental so that memory is not just a memory, but a commitment.

Source: vermelho.org.br