Published 01/11/2026 14:25

It was a hot Saturday when we took the bus to the Franklin neighborhood, in Santiago. We were anxious. We were going to visit Alejandro “Mono” González, recently awarded the Chilean National Visual Arts Prize, one of the most important cultural recognitions in the country. The visit was part of the special coverage of the Red Portal in Chile, carried out as part of the audiovisual project Caminhos da Revolution, which covers territories, spaces of memory and cultural experiences linked to popular struggles in Latin America and Europe.

The Franklin neighborhood has a history deeply linked to the world of work and Chilean popular culture. Formed from the old Public Slaughterhouse at the beginning of the 20th century, the territory has transformed over time into one of the largest centers of popular commerce in Santiago. It is there that Persa Bío-Bío was established, a huge fair that takes place mainly on weekends, bringing together clothes, books, records, food, antiques, art and unlikely encounters. A space where the city recognizes itself outside of formal circuits and where life happens without filters.

Also read: Chilean Memory Museum: art and human rights as democratic practice

The car couldn’t drop us off at the door. We got off two blocks earlier and continued on foot. The surrounding streets were completely filled with stalls selling clothes, food, produce and antiques. The flow of people was intense, mixing residents, workers, tourists and curious people. Between colors, smells and voices, the fair presented itself as a living organism. It was impossible not to notice that this scenario was in deep dialogue with the work and trajectory of Mono González.

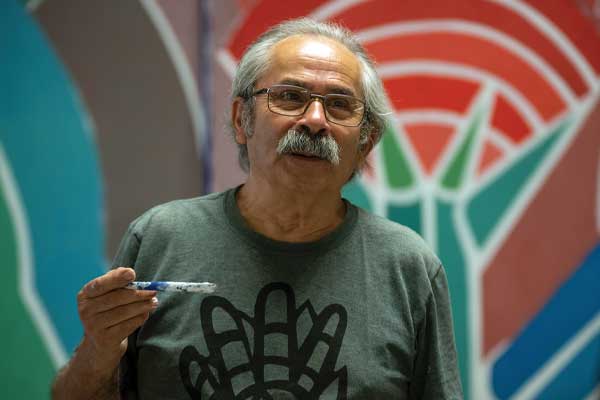

Unlike the sophisticated galleries and closed studios of many renowned artists, we arrived in a simple warehouse. On one side and the other of the corridor, boxes and displays were still empty, metal doors closed, as if the day was just beginning. It was then that we saw a man with white hair and a mustache, wearing a worn-out t-shirt and sandals, locking a door and, soon after, starting alone to hang works, pictures and books. No fanfare, no ceremony. It was Alejandro “Mono” González. One of the few who we can refer to, without exaggeration, as a genius.

We introduced ourselves, and he, with immediate friendliness, good humor and disarming simplicity, welcomed us and asked us to wait for about half an hour. I needed to tidy up the space, organize the works, prepare the gallery. After all, that was where he lived, from selling those wonders that, between paintings, engravings and books, carried decades of history, struggle and collective creation. We said there was no problem and asked if we could talk while he started work.

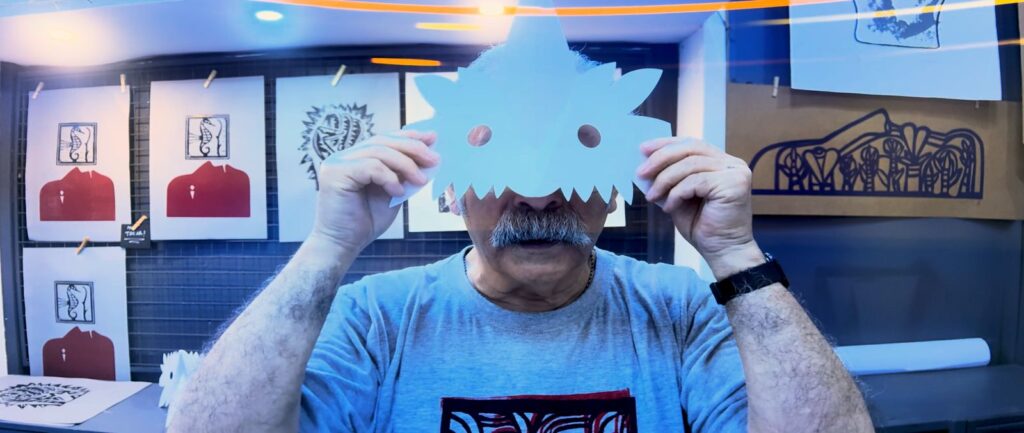

Opens drawers, climbs stairs, hangs posters. The conversation goes smoothly throughout the tidying time. During this interval, an assistant arrives to help him and, shortly after, his son, also an artist. The space gains even more life, functioning at the same time as a studio, gallery, workshop and meeting place.

The first customers start to arrive. Mono welcomes everyone with attention, talks, greets, explains the works, laughs, teases, serves everyone with the greatest good humor in the world. So, between arrivals and departures, we talked for almost two hours, without noticing the time passing. There was no separation between art and life there. Everything happened together, mixed, as it has always been in popular muralism.

Also read: Chile Stadium: memory, resistance and the permanent fight against oblivion

We were also lucky enough that, that Saturday, Mono was unveiling a large fabric mural, created in partnership with the artists from Malfatti Têxtil, a collective that develops beautiful work with dyed wool. The work, marked by symbolic force and popular aesthetics, is destined for the National Library of Chile, reaffirming the artist’s commitment to bringing art and memory to public and accessible spaces. The occasion also allowed us to meet the artists involved, further expanding the collective meaning of that meeting.

Throughout the conversation, Mono revisits his trajectory without any artificiality. It talks about Salvador Allende’s campaign, the creation of the Ramona Parra Brigade, the urgency of occupying public space with direct, accessible images, capable of dialoging with those who pass by. For him, muralism was always more than aesthetics: it was popular communication, political pedagogy and a narrative dispute.

The dictatorship inevitably appears as a rupture, but also as a period of silent resistance and reinvention. Mono talks about clandestinity, work as a set designer, art as a shelter and survival tool. Memory, in its speech and in its practice, is not a frozen past, but living matter, which needs to be permanently activated so that history is not erased, distorted or trivialized.

When the subject is the present, he connects muralism to contemporary languages, such as graffiti and urban arts, understanding everything as part of the same genealogy: the occupation of public space as a political gesture. For Mono, art that does not dialogue with its time runs the risk of becoming just ornament.

If we could define the encounter in a single word, it would be generosity. It is impressive to see how such a complete artist chooses to live his life in this way, far from the big chic galleries and without any trace of pose or vanity. Mono González is the rare synthesis of enormous artistic capacity, deep political engagement and a simplicity that cannot be staged, but only experienced.

Upon leaving Persa Bío-Bío, amid the noise of the fair and the comings and goings of people, it was clear that this meeting said much more than an interview. In the context of the special coverage of Portal Vermelho and the Caminhos da Revolution project, the visit to Mono González’s studio reaffirms that art, when rooted in people and memory, continues to be a powerful tool of resistance, identity and social transformation.

__

Source: vermelho.org.br